gRPC

Resource:

Overview

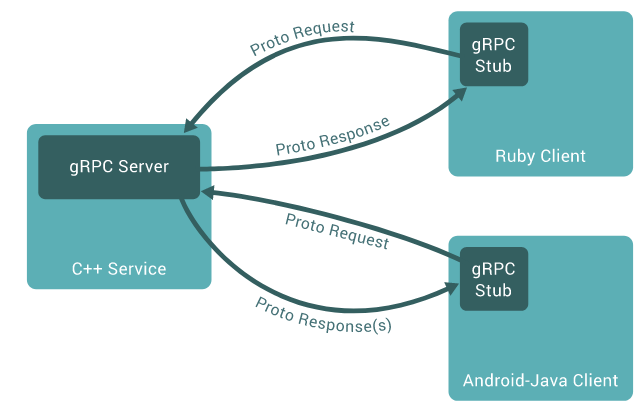

In gRPC a client application can directly call methods on a server application on a different machine as if it was a local object, making it easier for you to create distributed applications and services. As in many RPC systems, gRPC is based around the idea of defining a service, specifying the methods that can be called remotely with their parameters and return types. On the server side, the server implements this interface and runs a gRPC server to handle client calls. On the client side, the client has a stub (referred to as just a client in some languages) that provides the same methods as the server.

gRPC clients and servers can run and talk to each other in a variety of environments - from servers inside Google to your own desktop - and can be written in any of gRPC’s supported languages. So, for example, you can easily create a gRPC server in Java with clients in Go, Python, or Ruby. In addition, the latest Google APIs will have gRPC versions of their interfaces, letting you easily build Google functionality into your applications.

What is a protocol buffer

Resource:

Protocol buffers are a flexible, efficient, automated mechanism for serializing structured data – think XML, but smaller, faster, and simpler. You define how you want your data to be structured once, then you can use special generated source code to easily write and read your structured data to and from a variety of data streams and using a variety of languages. You can even update your data structure without breaking deployed programs that are compiled against the "old" format.

How do they work

You specify how you want the information you're serializing to be structured by defining protocol buffer message types in .proto files. Each protocol buffer message is a small logical record of information, containing a series of name-value pairs. Here's a very basic example of a .proto file that defines a message containing information about a person:

message Person {

required string name = 1;

required int32 id = 2;

optional string email = 3;

enum PhoneType {

MOBILE = 0;

HOME = 1;

WORK = 2;

}

message PhoneNumber {

required string number = 1;

optional PhoneType type = 2 [default = HOME];

}

repeated PhoneNumber phone = 4;

}

Each message type has one or more uniquely numbered fields, and each field has a name and a value type, where value types can be numbers (integer or floating-point), booleans, strings, raw bytes, or even (as in the example above) other protocol buffer message types, allowing you to structure your data hierarchically. You can specify optional fields, required fields, and repeated fields. You can find more information about writing .proto files in the Protocol Buffer Language Guide.

Once you've defined your messages, you run the protocol buffer compiler for your application's language on your .proto file to generate data access classes. These provide simple accessors for each field (like name() and set_name()) as well as methods to serialize/parse the whole structure to/from raw bytes – so, for instance, if your chosen language is C++, running the compiler on the above example will generate a class called Person. You can then use this class in your application to populate, serialize, and retrieve Person protocol buffer messages. You might then write some code like this:

Person person;

person.set_name("John Doe");

person.set_id(1234);

person.set_email("jdoe@example.com");

fstream output("myfile", ios::out | ios::binary);

person.SerializeToOstream(&output);

Then, later on, you could read your message back in:

fstream input("myfile", ios::in | ios::binary);

Person person;

person.ParseFromIstream(&input);

cout << "Name: " << person.name() << endl;

cout << "E-mail: " << person.email() << endl;

You can add new fields to your message formats without breaking backwards-compatibility; old binaries simply ignore the new field when parsing. So if you have a communications protocol that uses protocol buffers as its data format, you can extend your protocol without having to worry about breaking existing code.

Why not just use XML

Protocol buffers have many advantages over XML for serializing structured data. Protocol buffers:

- are simpler

- are 3 to 10 times smaller

- are 20 to 100 times faster

- are less ambiguous

- generate data access classes that are easier to use programmatically

For example, let's say you want to model a person with a name and an email. In XML, you need to do:

<person>

<name>John Doe</name>

<email>jdoe@example.com</email>

</person

while the corresponding protocol buffer message (in protocol buffer text format) is:

# Textual representation of a protocol buffer.

# This is *not* the binary format used on the wire.

person {

name: "John Doe"

email: "jdoe@example.com"

}

When this message is encoded to the protocol buffer binary format (the text format above is just a convenient human-readable representation for debugging and editing), it would probably be 28 bytes long and take around 100-200 nanoseconds to parse. The XML version is at least 69 bytes if you remove whitespace, and would take around 5,000-10,000 nanoseconds to parse.

Also, manipulating a protocol buffer is much easier:

cout << "Name: " << person.name() << endl;

cout << "E-mail: " << person.email() << endl;

Whereas with XML you would have to do something like:

cout << "Name: "

<< person.getElementsByTagName("name")->item(0)->innerText()

<< endl;

cout << "E-mail: "

<< person.getElementsByTagName("email")->item(0)->innerText()

<< endl;

However, protocol buffers are not always a better solution than XML – for instance, protocol buffers would not be a good way to model a text-based document with markup (e.g. HTML), since you cannot easily interleave structure with text. n addition, XML is human-readable and human-editable; protocol buffers, at least in their native format, are not. XML is also – to some extent – self-describing. A protocol buffer is only meaningful if you have the message definition (the .proto file).

Why the name "Protocol Buffers"

Resource: grpc.io/protocolBuffers

The name originates from the early days of the format, before we had the protocol buffer compiler to generate classes for us. At the time, there was a class called ProtocolBuffer which actually acted as a buffer for an individual method. Users would add tag/value pairs to this buffer individually by calling methods like AddValue(tag, value). The raw bytes were stored in a buffer which could then be written out once the message had been constructed.

Since that time, the "buffers" part of the name has lost its meaning, but it is still the name we use. Today, people usually use the term "protocol message" to refer to a message in an abstract sense, "protocol buffer" to refer to a serialized copy of a message, and "protocol message object" to refer to an in-memory object representing the parsed message.