Types

Static types systems describe the shapes and behaviors of what our values will be when we run our programs. A type-checker like TypeScript uses that information and tells us when things might be going off the rails.

While we could write a function in JavaScript that looks like this:

function add(num1, num2) {

return num1 + num2;

}

With Typescript we can add parameter type annotations so that we immediately get an error if we supply the function with the wrong argument type:

function add(num1: number, num2: number) {

return num1 + num2;

}

Primitive Types

JavaScript has three very commonly used primitives: string, number, and boolean. Each has a corresponding type in TypeScript.

The type names String, Number, and Boolean (starting with capital letters) are legal, but refer to some special built-in types that will very rarely appear in your code. Always use string, number, or boolean for types.

Object Types

Apart from primitives, the most common sort of type you’ll encounter is an object type. This refers to any JavaScript value with properties, which is almost all of them! To define an object type, we simply list its properties and their types:

// The parameter's type annotation is an object type

function printCoord(pt: { x: number; y: number }) {

console.log("The coordinate's x value is " + pt.x);

console.log("The coordinate's y value is " + pt.y);

}

printCoord({ x: 3, y: 7 });

Here, we annotated the parameter with a type with two properties - x and y - which are both of type number. You can use , or ; to separate the properties, and the last separator is optional either way.

Optional Properties

Object types can also specify that some or all of their properties are optional. To do this, add a ? after the property name:

function printName(obj: { first: string; last?: string }) {

// ...

}

// Both OK

printName({ first: "Bob" });

printName({ first: "Alice", last: "Alisson" });

Arrays

To specify the type of an array like [1, 2, 3], you can use the syntax number[];. You may also see this written as Array<number>, which means the same thing.

any

TypeScript also has a special type, any, that you can use whenever you don’t want a particular value to cause typechecking errors. When a value is of type any, you can access any properties of it (which will in turn be of type any), call it like a function, assign it to (or from) a value of any type, or pretty much anything else that’s syntactically legal:

let obj: any = { x: 0 };

// None of the following lines of code will throw compiler errors.

// Using `any` disables all further type checking, and it is assumed

// you know the environment better than TypeScript.

obj.foo();

obj();

obj.bar = 100;

obj = "hello";

const n: number = obj;

The any type is useful when you don’t want to write out a long type just to convince TypeScript that a particular line of code is okay. When you don’t specify a type, and TypeScript can’t infer it from context, the compiler will typically default to any.

You usually want to avoid this, though, because any isn’t type-checked. Use the compiler flag noImplicitAny to flag any implicit any as an error.

Tuple Types

A tuple type is another sort of Array type that knows exactly how many elements it contains, and exactly which types it contains at specific positions.

type StringNumberPair = [string, number];

Here, StringNumberPair is a tuple type of string and number. To the type system, StringNumberPair describes arrays whose 0 index contains a string and whose 1 index contains a number.

Union Types

A union type is a type formed from two or more other types, representing values that may be any one of those types. We refer to each of these types as the union's members.

Example of a function that can operate on strings or numbers:

function printId(id: number | string) {

console.log("Your ID is: " + id);

}

// OK

printId(101);

// OK

printId("202");

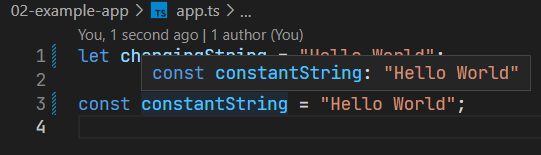

Literal Types

In addition to the general types string and number, we can refer to specific strings and numbers in type positions. This is reflected in how TypeScript creates types for literals:

It’s not much use to have a variable that can only have one value! But by combining literals into unions, you can express a much more useful concept - for example, functions that only accept a certain set of known values:

function printText(s: string, alignment: "left" | "right" | "center") {

// ...

}

printText("Hello, world", "left");

// Argument of type '"centre"' is not assignable to parameter of type '"left" | "right" | "center"'

printText("G'day, mate", "centre");

Numeric literal types work the same way:

function compare(a: string, b: string): -1 | 0 | 1 {

return a === b ? 0 : a > b ? 1 : -1;

}

Type Aliases

We’ve been using object types and union types by writing them directly in type annotations. This is convenient, but it’s common to want to use the same type more than once and refer to it by a single name.

A type alias is exactly that - a name for any type. The syntax for a type alias is:

type Point = {

x: number;

y: number;

};

// Exactly the same as the earlier example

function printCoord(pt: Point) {

console.log("The coordinate's x value is " + pt.x);

console.log("The coordinate's y value is " + pt.y);

}

printCoord({ x: 100, y: 100 });

It's similar to an interface, but it can't be extended - and it can represent things that interfaces can't.

void

void represents the return value of functions which don’t return a value. It’s the inferred type any time a function doesn’t have any return statements, or doesn't return any explicit value from those return statements:

function printResult(num: number): void {

console.log("Result: " + num);

}

object

The special type object refers to any value that isn’t a primitive (string, number, bigint, boolean, symbol, null, or undefined). This is different from the empty object type { }, and also different from the global type Object. It’s very likely you will never use Object.

Note that in JavaScript, function values are objects: They have properties, have Object.prototype in their prototype chain, are instanceof Object, you can call Object.keys on them, and so on. For this reason, function types are considered to be objects in TypeScript

unknown

The unknown type is the type-safe counterpart of any. Anything is assignable to unknown, but unknown isn't assignable to anything but itself and any without a type assertion or a control flow based narrowing. Likewise, no operations are permitted on an unknown without first asserting or narrowing to a more specific type.

let vAny: any = 10; // We can assign anything to any

let vUnknown: unknown = 10; // We can assign anything to unknown just like any

let s1: string = vAny; // Any is assignable to anything

let s2: string = vUnknown; // Invalid; we can't assign vUnknown to any other type (without an explicit assertion)

vAny.method(); // Ok; anything goes with any

vUnknown.method(); // Not ok; we don't know anything about this variable

There are often times where we want to describe the least-capable type in TypeScript. This is useful for APIs that want to signal “this can be any value, so you must perform some type of checking before you use it”. This forces users to safely introspect returned values.

never

Some functions never return a value:

// Function returning never must have unreachable end point

function fail(msg: string): never {

throw new Error(msg);

}

The never type represents values which are never observed. In a return type, this means that the function throws an exception or terminates execution of the program.